Prebid doing away with universal Transaction IDs is just the latest example of the ad industry’s counterproductive history of information asymmetry and obfuscation.

When both sides of a transaction aren’t working with the same information, you can’t have a fair market. Strong business relationships can’t be built on mistrust.

But to get to the heart of this TID debacle, you have to understand two things: the quintessential definition of a healthy marketplace and how our tendency to limit transparency for the other side of the supply chain is holding us back.

A healthy marketplace is a transparent marketplace

Lack of transparency has been part of programmatic advertising nearly from the beginning.

To understand this struggle, it’s important to understand the early days of real-time bidding.

Back in 2007-2008, I was an SVP and GM at MySpace (aka the Fox Audience Network, or FAN), which, at the time, had over 275 million global users and 60+ billion ad impressions a month.

Audience buying was called “retargeting,” and it was largely done by behavioral ad networks: Tacoda, Revenue Science, Criteo and Right Media Exchange. All of these entities ran in ad tags in the FAN ad server waterfall.

These companies told us they’d be willing to buy our audiences at $8-$25 CPMs. Some even offered to pay $100 CPMs for limited campaigns.

Eureka! This demand was the inspiration we needed. We had to increase yield, so we created a client-side way to call each retargeting network first, before we called our ad server waterfall. Then we conducted the auction.

However, this client-side bidding (which was the precursor to header bidding) didn’t scale; it had to be moved to the server.

The decline of MySpace as a social network coincided with the era of SSPs and ad exchanges enabling server-to-server connections with other emerging technologies on the demand side: namely, DSPs and retargeting networks.

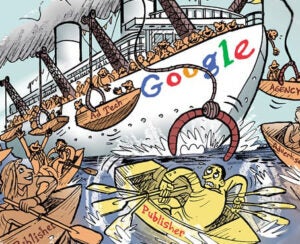

With this shift to server-to-server integrations, campaign decisioning moved to the demand side, as these platforms enabled advertisers to make bidding decisions based on their first-party data. Plus, let’s face it, the demand side held the budgets and, thus, had all the leverage.

A new model emerged: The buy side RTB platforms enabled data-based decisions, conducted their own auction, cleared the winner and shared the winning bid with the sell side. Obfuscation of bidstream data started here.

What publishers don’t see

To effectively sell their inventory, publishers need transparency into pricing and demand.

But from a supplier point of view, there actually aren’t that many bidders on a single impression. Once the auction moved to the demand side, publishers received bids from, at max, two or three “uber bidders” – aka the large DSPs.

DSPs clear their tonnage of advertiser bids, but none of this data is disclosed to the supplier via its SSP – just the winning bid.

The SSP has no insight into how many advertisers bid, who they were, what their bid price was or what cookies or other audience identifiers they were interested in. Even Google Ads doesn’t provide this transparency. All the advertisers are aggregated and anonymized.

This status quo falls well short of a healthy marketplace, which requires robust competition, transparency and a system of governance that protects participants. It also calls for efficient flow of information and limited barriers to entry to allow for a dynamic environment, where buyers and sellers can transact with confidence.

Here’s what the industry needs to fix before we can level the playing field:

- Competition: A sufficient number of buyers and sellers can prevent a monopoly in which a single entity manipulates prices. If the supplier is only seeing one, two or three bids per impression, then the supplier doesn’t see enough liquidity and bid density to intelligently price its inventory.

- Transparency: To make rational, informed decisions, all market participants must have easy access to accurate and timely information. This includes details about prices, quality, product content and company practices. In the programmatic marketplace, the supply side doesn’t have access to buyer information, nor do we have insight into the fees that the vendors on the buy and sell side take. This is information asymmetry.

- Trust and security: A strong system of governance is needed to ensure a safe environment for transactions. This means security certifications, protection for customer data and tools for dispute resolution.

The chicken and the egg on obfuscation

Because the industry has been slow to address the above, the supply side has taken its own measures to right-size gaps in information and bid density.

The obfuscation that plagues the bidstream didn’t start on the supply side, though. Information asymmetry occurred first on the demand side, which is how header bidding came to be used as a supplier weapon in the battle to find the right price.

But when header bidding created more liquidity of bid density, this necessitated the demand side to throttle queries per second and stem the flood of bid requests coming in.

The auction duplication inherent to header bidding then led to supply-path optimization, because why would an advertiser want to bid against themselves? Transaction IDs became a necessary instrument to solve the duplication issue.

The counter measure from the supply side is to obfuscate the TID. Net-net, we find ourselves back to the beginning.

Perhaps much of this gets solved with the demand side moving closer to the supply side. Maybe SSPs handling deal curation and DSPs going direct to publishers will create a healthier, more trusting marketplace.

That way, we can stop reenacting the scene in “Grosse Pointe Blank” where Cusack and Aykroyd roll up to a meeting with their hands on their guns and instead share information and shake on it.

“The Sell Sider” is a column written by the sell side of the digital media community.

Follow Mula and AdExchanger on LinkedIn.

For more articles featuring Jason White, click here.