AI has a tendency to generate false information in response to queries and present it as fact – which is a bad thing, right?

Not always, according to Springboards, a self-described “creative AI tool” designed to generate inaccurate information for the sake of sparking creativity.

Instead of trying to reduce hallucinations, Springboards is leaning into them, purposely generating the most out-there (and factually inaccurate) outputs it can.

“When I’m looking for inspiration, I want ideas that are outside the norm,” Pip Bingemann, CEO and co-founder of Springboards, told AdExchanger. “I want outliers.”

Springboards isn’t just trying to bring about creativity with its own tools; it’s also helping users determine which AI models are best suited for their own creative needs.

Springboards’ new Creativity Benchmark test – backed by a number of advertising associations, including the 4As and the International Advertising Association – aims to assess an AI’s ability to inspire creativity. Some of the criteria include creative variance of outputs, problem-solving abilities and human judgment of the ideas.

Swipe right

Large-language models have historically been trained to succeed in situations where there is a right and a wrong answer, like on a science test or legal exam.

But there isn’t one tool that can accomplish every task, Bingemann said. A wrench might be incredibly helpful for a plumber fixing a leaky pipe, but if you give a journalist that same wrench, she’s unlikely to find it very useful in writing a news story. (We can attest.)

Hallucinations, however, can introduce unexpected variations and novel twists, which, in a creative context, is often the goal.

Springboard’s platform offers what it refers to as a “Tinder for ideas”-style experience, whereby users are presented with different creative outputs from AI models and can select their preference. They do this over and over, until the system has a clear idea of what AI model best suits their individual preferences.

With time, Bingemann hopes to evaluate trends and preferences on a “macro level” and across industry, job title and geographic location.

“We’re not trying to quantify creativity,” he said. “We’re trying to quantify which models are the best at inspiring creativity.”

Reaching record highs

But inspiring creativity isn’t the same as generating a creative strategy. Springboards intends to “keep humans in the creative equation,” said Bingemann. “We don’t want to replace anyone.”

Indeed, without human analysis and creativity, the tools that Springboards has developed, including one called “Insight Digger,” wouldn’t go very far.

Insight Digger was built on what Bingemann described as “a milkshake of LLMs” including Perplexity, OpenAI and Gemini. It serves as a canvas that generates inspiration for brand strategy, execution and creative with over 10 times more variance than OpenAI, Anthropic and Gemini combined, he said.

Bingemann used Lay’s potato chips to demonstrate how the tool works. Initially, when prompted, it suggested “crunchy, sociable, upbeat, tempting and familiar” as options for tone of voice. (Not sure what a crunchy tone is, but sure.) The brand history it offered was similarly straightforward and also accurate: “Lay’s began as a humble snack peddled by a visionary entrepreneur out of the trunk of a car” and so on.

But who needs AI to figure that out?

“If you really want to dial up the hallucinations,” Bingemann said, Springboards has a “randomness” scale that, when turned on, has three levels: micro-dosing, LSD and Asylum. (Yes, really.)

Using the Asylum setting, things definitely get quirky, with suggestions for tone of voice ranging from “galactic” and “crunchtastic” to, inexplicably, “socks!”

For brand history, the tool concocted the tale of a monocle-clad “Sir Spudington” going skinny dipping in a vat of oil.

Seeing isn’t believing

Users need to be careful trusting the tool’s outputs, though. When asked if the brand history function is accurate when the randomness dial is turned off, Bingemann simply said, “Sometimes it is; sometimes it isn’t.”

For example, once he turned the dial from “asylum” back to zero, the history section said that Lay’s was created in a barn, rather than sold out of the trunk of a car.

There is something to be said for an AI product that doesn’t produce identical results every time the same prompt is given. For example, if you ask any standard AI model to generate a random number between one and 10, Bingemann said, it will almost invariably produce seven.

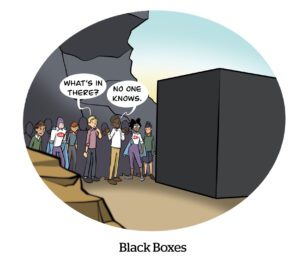

But it can be challenging to always have to question what to believe – or not believe – and to determine which of a tool’s outputs are genuine versus just a good laugh.

And although its aim isn’t to take human jobs away, there’s also an argument that attempting to randomly generate creative inspiration dilutes the human brainstorming experience. How much credit do you owe the machine that created Sir Spudington?

But Bingemann doesn’t seem too concerned.

“If we ever let the machines take over, I actually don’t think it’s going to work,” he said. For instance, a machine hasn’t experienced heartbreak or joy and so can’t truly understand emotions, he added.

If machines were singlehandedly designing brand creative, sure, the images might look nice and production costs could decrease, but the real heart of media would suffer.

“My fear,” he said, is “a world chasing cheaper outputs at the cost of blandness.”